Urgent need to address alternative modes of architectural practices for Goa

Architect Arijeet

Raikar, one of the resource persons for the workshop organised by the Indian

Institute of Architects - Goa (IIA), impressed upon the audience that it was

possible to build a first-rate residence for a family within rupees seven

lakhs. The problem though is that it is financially unviable to run this kind

of an architectural practice within the existing ideology of practice, where

the norm is that the architect’s fees is a small percentage of the total

project cost. Enabling such alternative practices, with commitment from

architects as much as from the State, would go a long way to satisfy the

housing needs of the locals as well as the design challenges enjoyed by

architects. Ensuring employment opportunities to young architects while

continuing to address the specific needs of development in Goa will require the

change in the architecture of practice itself.

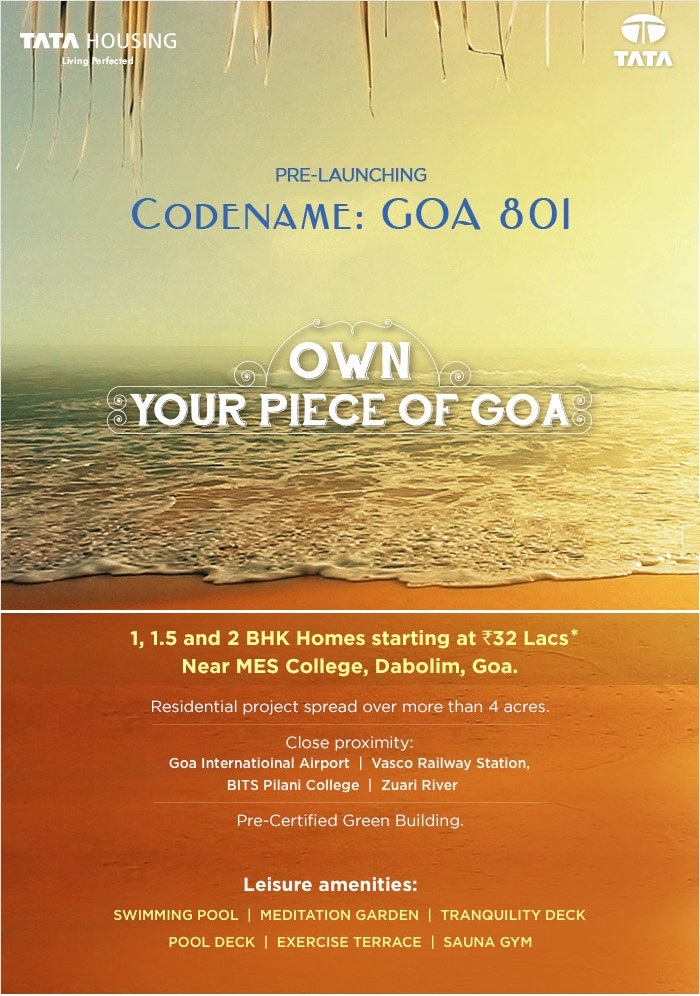

Goa is undergoing rapid and uncontrolled urbanizations, which are largely guided by the aspirations of elites from Indian metropoli. The Indian elites who buy second-homes in Goa are not here to settle. They are here to consume Goa and move on to greener pastures when the going is not good and the green is gone. In the 1980s and ‘90s, it were the super-rich who started the trend of buying second homes here. Since the turn of the century, with the liberalisation of the Indian economy and the boom in the Indian middle-class, this trend has changed and many more are acquiring second-homes here, making Goa their weekend getaway. Clearly, the focus has moved from merely enjoying Goa for its sights to the ownership of sites, in the form of real-estate properties.

Most professionals

assume that faster development will lead to bigger employment opportunities,

seldom realising how the capitalist economy works. In his article,

“Trickle-Down Economics -- The Most Destructive Phrase Of All Time?” (Forbes,

6 Dec. 2013), George Leef, writes that “[i]n a free society, wealth doesn’t

trickle down, or up, or sideways. It is earned. What people … don’t understand

or won’t admit, is that people of all economic strata, and no matter their

race, religion, sex, or anything else, have far more opportunities to earn in a

society with a small, efficient, frugal government than they do in a society

with a huge, wasteful one.” This line of thinking is critical to Goa and especially

for practicing architects. The impetus given to large-scale development

projects in Goa is usually in the hope that there will be a trickle-down

effect. Local Goan architects for

instance are under the illusion that the trickle down economy is going to cater

to their needs, and deliver to them some projects. We passively allow economic

policies to be thrust on us, hoping against hope that some of the project

opportunities will trickle down to us. The grim truth is, they seldom do,

except maybe to a few cronies of those at the helm.

At another level, architect Rahul

Mehrotra, the keynote speaker at the recent Z-axis conference in Panjim, highlighted

that, today, the State’s contribution to the neoliberal economy has been

restricted to the development of infrastructure, such as highways, flyovers,

expensive bridges, and so on, which are meant to benefit corporate projects,

while the important “mainstream” projects like housing have been left to the

mercy of private developers. Architects, he rued, are either co-opted by these

developers, or contend with boutique practices like designing luxury second

homes. While the developers’ practice is that of crunching numbers to maximise

the saleable spaces of apartments, the boutique practice has become the

practice of indulgence, both on behalf of the elite client as well as the

architect. Mehrotra also identified the media as being guilty for encouraging

glamourized boutique practices by creating signature ‘hero’ architects. Usually architecture practices as represented

in popular lifestyle magazines largely represent the projects commissioned by

the rich. Today, it is important to break this hegemony of the popularly

accepted ideal architectural project like luxury second-homes, so that new

categories of practice emerge, categories which address the unique development

model that Goa requires.

(This article is based on the

keynote address I gave on ‘Refiguring the Architecture of Practice’ at a

workshop organised by IIA Goa on the occasion of World Architecture Day.)

[This article was published on The Goan on 23/10/2016.]